Notes from a Crusty Seeker

Oh Reader—Oh, What a Gift!

I'm a voracious reader as well as a writer, and therefore a lot of my journalism these days focusses on books.

I knew nothing about Oh Reader magazine except that they might be open to articles I'm interested in writing. And I was thrilled when editor Gemma Peckham accepted a piece about finding hilarious books by female writers. She has published it, under the title "Laughing with the Ladies," in the December 2022 (issue 010) Oh Reader and, oh boy, am I surprised and grateful for the discovery of this magazine.

I just finished reading it cover to cover, and this is a reader's heaven.

Of course, I like my own piece, detailing the difficulty of finding pee-in-your-pants funny books by women, why that has been a problem, and a list with short descriptions of the 13 books that I've discovered since I began my quest eight years ago.

But there's more.

My favorite stories: how being raised Hindu affected the writer's (Thulasi Seshan) reverence for physical books; the story of a neighbor's book collection and how reading it after her demise affected the author (Rebecca Duras); a fittingly short essay by a writer (Steven Allison) who couldn't read due to his ADHD about the unlikely way he learned he can read whole books; and a deeply moving contemplation by a bookseller (Laura Bridgewater) about what she learned was the true gift of the bookseller-customer interaction.

Not only are the articles wonderful, but the art, layout, and high-quality paper make this a magazine to save.

The December issue will be on magazine stands on December 8, 2022, and you can learn more at Oh Reader.com.

@betsyjuliarobinson A great magazine for readers #booktok #reading #books @ohreadermag #magazintiktok #readers ♬ original sound - Betsy Robinson

Vote Like Democracy Depends on It . . . Because It Does

I sought this novel out after reading Kathrine Kressmann Taylor’s perfect goose-bump of a short story "Address Unknown." That story, originally published in 1938, received much-deserved notoriety in its time and was later republished as a stand-alone paperback with an afterword by the author's son giving the back story of this riveting epistolary exchange between two Germans, one a Jew and one a budding Nazi, at a pivotal time in history. It is an international best-seller.

I'm guessing Kressman Taylor's son, Charles Douglas Taylor (who contributed back-of-book comprehensive and illuminating histories about and by the real man* on whom Day of No Return was based), was motivated by the short story's success to self-publish (through Xlibris) this 2016 American edition of this out-of-print novel that has only four reviews on Goodreads. I would like to remedy its unmerited obscurity.

Day of No Return, first published in 1942, is equally necessary and horrifying. And it should be read by Americans who love democracy and are frazzled by our current history. If you enjoy reading history, this novel may be for you. I'll explain:

I was not brought up with a religion and one of the good parts of that is that I have no sense of any religion being superior and am comfortable with a live and let live attitude. But this background has also made me obtuse to the dynamism of religious fervor and power and how it can be used to take over and demolish democracy. For all its flaws, our Constitution and the founders were absolutely brilliant in their proclamation of a republic with a separation of church and state—a separation which insidious forces are eroding as I type.

The similarities of the trajectory of Germany into a Nazi regime and what's going on now in the USA are unmistakable. But without the knowledge of the historical precedent, we Americans are missing the chance to do a course correction. Read More

10 Books to Help You Cope with Cultural Agony—The Healing Power of Fiction

Yesterday my book club discussed Jason Mott's National Book Award-winning hilarious, heart-breaking novel Hell of a Book, a story of an unnamed Black man's life in a world where he is never seen as who he knows himself to be. What was most meaningful for me was that by the end of our discussion, this white not-particularly-contemplative group of older women settled into a profoundly personal conversation about self-acceptance.

All fiction, when done well, forces you to walk in another person's shoes … or into deeper levels of the shoes you are already wearing. And because of this, fiction can take the reader on an emotional journey to healing or coping with pain that may seem intractable.

What the following ten stories have in common is accepting realities that are personal as well as historical. Racism, genocide, spousal abuse, and more. How do you accept these things? These books leave little alternative. And by dealing with what's true, there is a form of healing, or at least a path to coping. The human journey is just that—no matter what your race, gender, or status—accepting truth on all levels.

But what is truth in these days of divided definitions?

When I say "truth," I am referring to what Ernest Hemingway meant when he advised writers to ". . . write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence you know." To me this means truth that comes from one's core. One's Essence—however you define that. It isn't about politics or disinformation vs. fact.

When a writer's Essence births a true story, it is told through true characters, and no matter how fantastical or removed from your life they may be, almost everybody can identify in some way and have a personal experience. That personal experience can sometimes be love or a refusal to love, which can manifest as an emotional aversion. If we hate, rather than blame the story, we can follow the aversion down to its root and perhaps learn something about ourselves—learn what we are refusing to accept. And if we can love the truth about ourselves, loving all the other stuff gets easier. Read More

Compassionate Death

It's 8:12 a.m. As I type, my body clock is confused but slowly readjusting to not lurching out of bed at 5:30 a.m. with my almost-16-year-old dog who would need to pee because she was getting daily IV saline drips for old-age kidney disease, to not timing everything from 5:30 a.m. on to her meds and pee and sun-downing blind frenzy that began each day around 5:00 p.m., to not really sleeping for the 15 months of her hospice care.

I do not regret one second of this exhausting schedule. It was an honor and what I wanted to do. The pandemic actually made my life easier—more acceptable. It was just Maya and me for the last year+ and I cherished every minute of it.

But Monday night, she let it be known she was done, and Tuesday morning Wendy McCulloch, DVM (Pet Requiem, LLC) came to the apartment, listened to my explanation about Maya's condition, and was an invisible angel, barely rousing Maya, who had uncharacteristically chosen to go back to bed after our early-morning ablutions, and sent my girl on her way. It was as peaceful and smooth a transition as I could imagine.

I'm being similarly gentle with my own transition to a solo life but I found myself twice yesterday declaring to people that I want the same treatment that I and Dr. McCulloch gave to Maya. And suddenly it seems very necessary to declare it in a public forum.

I am about to turn 71 years old and am in great shape due to daily exercise, a vegan diet, and my four flights of stairs; I can carry 30 pounds of groceries up them without panting. I am vaccinated and boosted because to me that seems like a no brainer, but since a debacle in 2012 that I will explain in a minute, I stopped going to doctors and have opted out of the regular preventive checkups relentlessly pushed by my ever-phoning health carrier, and since I think my medical care is my own business, I have refused to get into a conversation to explain myself to them.

I will now explain myself: Read More

"Hell of a Book" by Jason Mott

11/18/21 Update: It won the National Book Award last night. Never has such a worthy and necessary great American novel received this kind of recognition at the perfect time the world needs to read this miraculous book!

Original Post:

How on earth do you review or even talk about such a devastatingly funny and shattering work of art? How can you begin to convey the nature of a story that tells the untellable?

I haven't a clue. So instead I'll tell a story I can tell:

About forty-five years ago I was grocery shopping in Food City, the long-gone supermarket at the corner of my block, West 70 Street, and Columbus Avenue. I was standing in the checkout line when an old pasty-faced White man came storming in, yelling, "Nigger! Niggers!" and slathering hate like a sudden tsunami of mucous. Like most of the people in the store, I was (and am) White. I think I stopped breathing, hoping he'd come nowhere near me and would leave soon. No management showed up to see that that happened. This is New York, they probably thought if they even noticed. Another whack job.

About a minute after the pasty-faced whack job entered, three little boys with bikes came trundling in, laughing and talking. They were maybe 10 and 8. Instantly the manager told them they couldn't bring those bicycles into the store, so the two older boys sent the 8-year-old to stand with the bikes outside the entrance while the 10-year-olds picked up snacks.

I paid for my groceries, exited the store, and I think resumed breathing. But not for long. Thirty seconds behind me, the pasty-faced nut job exploded out of the store, and seeing the little boy with the bikes, yelled, "Nigger!" either spitting or doing it with such force that the child almost fell over. And then he, the man, took off.

This is not my story—it is the boy's; but to completely tell it I have to say what I did: I about-faced, and took care of the little boy until his friends came out of the store. I told him all sorts of things about how the man was crazy and we were all just waiting for him to leave, and there was nothing wrong with the little boy and he should not for one second imagine that this craziness had anything to do with him. Then I asked permission to stand next to the boy until his friends came out. He nodded, speechless; in fact I don't recall him ever saying a word. But I will never forget his shocked saucer eyes. And I will never forget his numb nod once his friends came out and I asked if he would be okay now. And I will never forget a moment of devastation I witnessed and the ripples of damage that came before it and would go on and on and on that I could do not one damned thing about.

This is not a story about me. It is a story about that boy.

And Jason Mott figured out how to tell it. My heart is both broken and grateful.

The Travels of Jaimie McPheeters and How He Helped me Re-meet My Father

WHAT I READ MATTERS

I mean this title sentence every which way you can read it.

I'm guessing most people will receive it with a glib, "Of course, what you read matters; it influences what you believe."

But I mean this sentence much more expansively: What I read, the physical form of it, really matters. As does reading it (as opposed to listening to somebody else read a text). I care who may have owned or touched the book before me, and any history I may know attached to the book affects my reading experience.

I spent this week reading a 75-cent, paperback of The Travels of Jaimie McPheeters, Robert Lewis Taylor's Pulitzer Prize-winning 1959 novel about a 14-year-old relentlessly smart-alecky (and sometimes very funny) boy's picaresque adventures during 1849, following his pipe-dreaming gambling doctor father across the country to find gold in California.

If I were reading Jaimie McPheeters as an ebook, I might have abandoned it at the first mention of "darkies" because I just don't have the stomach for this in 2021. If I were reading a shiny new edition paperback, same thing. Yes, the writing is good, I might have reasoned, but why subject myself to casual racism and so many words? The book is of a bygone era and style.

But I'm reading the cracked brown pages turned and read by my father on his suburban commute to and from his job in New York City in 1960. I know this because I found his train ticket stub, used as a book mark, on the last page, and I know he loved this book because he once told me he did. Probably that's why I grabbed it from my mother's last house several years after my father's own pipe dreams and addictions imploded and he stuck a gun in his mouth. And it's why the book has stayed on the top shelf in my apartment since 1973.

I'd been eying it for months while I did my aerobic workouts. The spine drew me. I even got up on a ladder a few months ago to see what it was and when I saw, I remembered Dad's smile and joy when he said it was a really good book. I'll read that, I thought.

And it took until this week, months after the first beckoning, for me to pull it down and wipe off the dust bunnies.

When I lie on my couch and read this book, I know I'm touching something my father thought was good. I know that when he read this he was the sane, loving man who loved to read and loved the fact that I loved reading too, even though we had almost nothing else in common. Read More

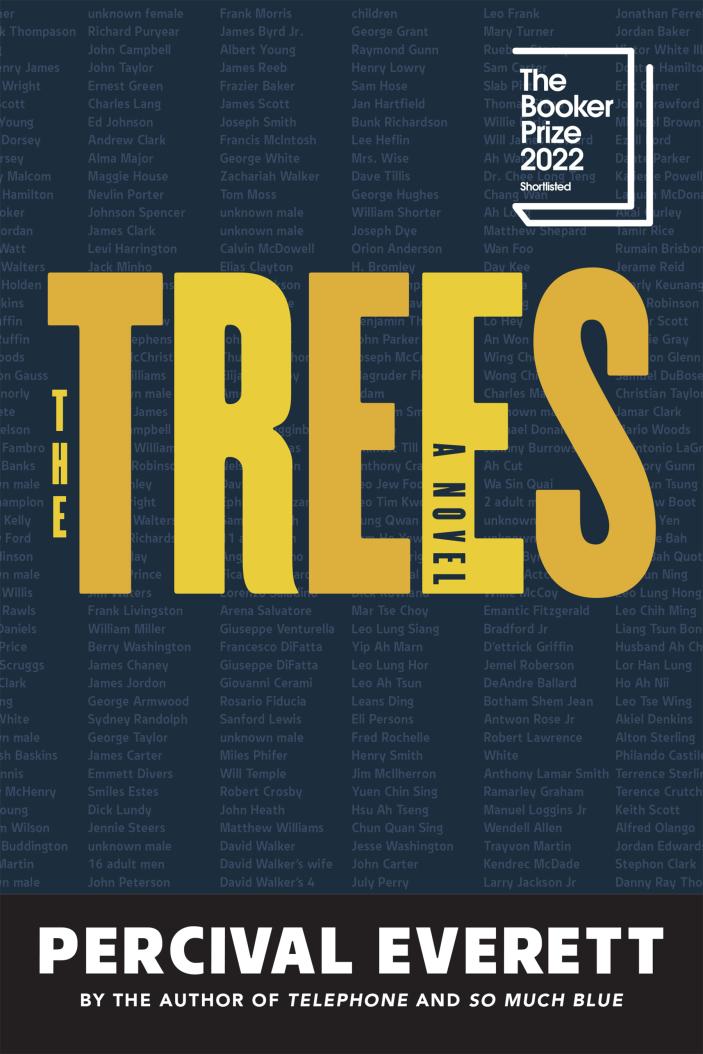

Standing Ovation for Percival Everett's "The Trees"

Percival Everett writes books that absolutely need to be written, and although my introduction to him was his dramatic novel So Much Blue, I somehow intuited the inside zaniness married to a skydiver’s sense of adventure and a philosopher’s wisdom and fearless vision of truth because my head exploded on first contact: “This is it!” screamed my hair follicles. “This is who I’ve been looking for.” And I hadn’t even read I Am Not Sidney Poitier, Glyph, or the incredibly prescient God’s Country, all of which made me scream with laughter and almost roll off my couch in joy and agony.

Reading The Trees after reading a lot of Everett’s 30+ books allows you to secretly smack your lips, knowing some of the precursors to this new one. Almost immediately I thought I knew what was coming because I’d read American Desert, and the ending to one of my favorite Everett books, the aforementioned God’s Country, has echoes of this new book, and almost seems to demand that it happen eventually. And now it’s here.

To compare Everett’s work to anybody else’s is pointless. So instead, here’s a scene that conveys what I love here and in his earlier funny novels (no setup necessary):

The Doctor Reverend Cad Fondle was sitting in his living room with his wife, Fancel. Fancel was a big woman, big enough that she hardly ever moved from her corduroy recliner, which was stuck in recline. There was a half a meat lover’s pizza and two beers on the foldout tray between her recliner and her husband’s. They were watching television, switching back and forth between Fox News and professional wrestling.

“They’s right,” Fancel said. “That Obamacare don’t work worth a hill of puppy shit. We done bought in, causin’ we had to, and I ain’t lost nary a pound.”

Fondle took long pull on his beer. “Well, the country’s done with that experiment. Smart-ass uppity sumbitch. You know he thinks he’s better’n us.”

“That Hannity is cute,” Fancel said. “If I could get my hand anywhere near my vajayjay, I’d rub me one out just watchin’ him.”

“You can’t reach it, so shut up.” Read More

The Reckoning: Our Nation’s Trauma and Finding a Way to Heal by Mary L. Trump, Ph.D.

There is something medicinal about hearing straight truth. With no affiliation to anything but the truth, clinical psychologist Mary L. Trump writes with muscular clarity, scholarship, and fury about anybody who acts in denial of the truth—from the beginnings of the practice of enslaving and torturing Black people to Obama and his justice department refusing to prosecute the architects of the Great Recession to the wanton cruelty and pathological lying of her uncle Donald to the January 6th insurrection to Joe Biden and Kamala Harris stating that this is not a racist country even though there is systemic racism. Even the Supreme Court and Jimmy Carter don't get away without condemnation.

Mary Trump writes with the heat of a wildfire and truncates American history in a way that makes its carefully crafted hypocrisy even more shocking. There is not a lot of new material if you've been educating yourself with whole history (as opposed to filtered white history) and if you follow the news. That said, if you haven't been reading book after book on racism, antiracism, and the history of racism, this is an excellent summation and exposure of the creation of ongoing systemic racism. But whatever your level of education, you will benefit from the passion of the writing steeped in scholarship and the laser focus that makes this book vibrate.

It is a book about the historical creation of our national trauma. Trauma comes not simply from the brutality and torture of slavery and genocide done with impunity that form the foundation of the U.S.A., but it comes from many "good" people looking the other way because the inconvenience of addressing and redressing the wrong was/is just too damned hard. It comes from denial and lies to justify the unjustifiable. It comes because people are reluctant to give up anything—money, power, complacency, peaceful co-existence with people who would be offended if they rocked the boat, "willful blindness. (115)" And all this was there long before it manifested Donald J. Trump.

The introduction to The Reckoning is one of the best book intros I've read. In it Mary Trump recounts her own history of PTSD and going into a full crisis that led to a stint in a rehab treatment facility after the election of her uncle. All that along with her grounded knowledge of psychology bring something unique to the book—well served by the fact that she is such a good writer.

This is not a "Trump book." It is an us/U.S. book. It is a fearless demand that we Americans look at who we are, who we have been, how we birthed the current divisions and violence, and acknowledging the wrongs, atone and repair. Read More

Books to Inspire Good Writing—Learning by Osmosis

I didn't go to grad school because frankly it never occurred to me. At the age most people enroll in MFA programs, I was zipping around NYC auditioning for acting roles and writing short stories and plays in my alone time. I didn't talk much about the writing, but once I mentioned it to a colleague when I had a menial job at an arts council and he asked why I didn't write a novel. Glibly but honestly I replied, "Because I'm too young." I knew I had so much to learn that I didn't even know what I didn't know, so certainly I wasn't mature enough to write a novel.

Now that I'm an old writer with some published novels, even though I still struggle to get my work seen and have none of the foundation contacts that MFA students start building during their student days, I'm still glad I took a different route.

I read voraciously and though some MFA grads produce good work out of the gate, I find many such first novels to be a little forced and self-consciously literary—the kind of thing that I associate with workshop students being praised by a teacher and one another for finding their original voice, for crafting esoteric observations, for being imaginative. And this group reinforcement results in a kind of groupspeak of self-conscious vocabulary and "insights" as well as endless stream-of-consciousness literary-sounding lists that I hear in my mind's ear in the droning monotone affected by certain writers giving readings of their work.

I've learned my craft and continue to learn by osmosis—by reading fine writing and getting feedback on my work from individuals I trust. Also, earning my living an editor of other people's work has been a boon to my own. I notice things as an editor does and, when inspired, steal like a pickpocket, morphing inspiring bits in the throes of my own creation so that you would never recognize their source.

Here are a few books that have been my teachers. Read More

The Passenger: People See What They Decide to See and Make Drastic Judgments

I usually only post book reviews of books that won't leave me alone. I thought, and hoped, that when I finished reading The Passenger by Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz, I was done with it. Since I closed the final page, I've gone to a book club meeting where we discussed another book and I'm reading my third new book. But Boschwitz won't leave. Hence, here's the review:

The Passenger

Otto Silbermann, with his Aryan nose but his Jewish last name is on the run. Although he's just been excoriated and demeaned by his Nazi business partner, he managed to get some of his money back. However he's stuck:

Mulling over his situation, he wondered what am I supposed to do now? Because they're still going after Jews. I can't stay a single night in my apartment—not with forty-one thousand marks!

We have to leave Germany, but no place will let us in I have enough money to start a new life, but how to get it out of the country? I don't have the nerve to try to smuggle it across. Should I stay or go? What to do?

Should I risk ten years in prison for a currency offense? But what other choice is there? Without money I'd starve out there. Every road leads to ruin, every single one. How am I supposed to fight against the state?

. . .

Other people were smarter. Other people are always smarter! If I'd realized in time what was going on, I could have saved my money. But everyone was constantly reassuring me. Becker [business partner] more than anybody. And fool that I am, I let myself be reassured. . . .

Maybe things aren't half so bad, and the whole business is one big psychosis. But no, I should finally acknowledge the reality of the situation: things are going to get worse—much, much worse! (80-81)

It's 1938 and Otto Silbermann, a persnickety neurotic, could not be less suited to running for his life.

Author Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz (1915-1942) wrote and published an earlier version of The Passenger when he was only 23, and he died before he could get a revised edition to his publisher. At first the writing seemed to me to have some of the clumsiness of a young writer—overwriting, heavy-handed dialogue, redundancy—but as my anxiety grew (more on that in a second) so did the writing grow on me and I stopped judging.

PERSIST by Elizabeth Warren

I don't have kids and have never dealt with the difficulty of getting good, affordable childcare, but by the end of the first chapter of Persist, I cared so passionately about national childcare that, typing this sentence while eating a carrot, I got excited enough to swallow the wrong way and had to lurch from my desk to open my airway.

How is it possible to explain the tax code, tax deductions, and how business is constantly subsidized by all of us (aka socialized wealth distribution; what people are so afraid of is already going on, but the recipients are large corporations and billionaires!*) so clearly that the reader has an aha about the movement of money in the economy resulting in a feeling that she can articulate life itself: all life is movement and change, and Warren ties that to the economy so simply and coherently that you will never not understand this again, and hence, never not understand inequity of investment that is built into our system and an imbalance that will eventually topple us all if not corrected.

Simply put, Elizabeth Warren is a great teacher. I understand why Rep. Katie Porter changed her life while taking Warren's class (a wonderful anecdote). As I type this, I'm now in the middle of an explanation of a two-cent wealth tax and what that would mean and how it would work, and again, it's so exciting, I'm chewing my carrot extra carefully in order to stay at the computer.

One of my other favorite teachers, Bertice Berry, recently did a video about how being your authentic self brings light to all situations and people, so if another person who is not being authentic is illuminated in that light, it can expose them and make them really angry. I thought of this when Warren first talked about former Mayor Mike Bloomberg. I remembered her stunning exposure of his arrogance during the presidential debates (deliciously reported later in the book in a chapter called A Fighter). In that moment she exposed her authentic brilliance in a way that constantly flows through this well-made book.** Read More

Why I Support Changes in American History Education

According to Heather Cox Richardson’s “Letters from an American” enews this morning (dated May 2, 2021):

On April 19, the Department of Education called for public comments on two priorities for the American History and Civics Education programs. Those programs work to improve the "quality of American history, civics, and government education by educating students about the history and principles of the Constitution of the United States, including the Bill of Rights; and… the quality of the teaching of American history, civics, and government in elementary schools and secondary schools, including the teaching of traditional American history." The department is proposing two priorities to reach low-income students and underserved populations. The Republicans object to the one that encourages "projects that incorporate racially, ethnically, culturally, and linguistically diverse perspectives into teaching and learning."

I couldn't check out the public comments portal fast enough.

I am seventy years old. It was not until around twenty years ago when I found myself working for an organization that had indigenous rights projects that I realized millions of people all over the world had worldwide conferences and had been screaming (and ignored) for centuries about land theft, culture obliteration, and the destruction of their families. I met many of these people and felt as though I'd been living under a rock all my life. This led to a self-education project that escalated during the Trump era when racism became acceptable. I've read book after book (see end of this essay for references*) that horrified me at what my white school never taught. I felt embarrassed and also infuriated at the blatantly false history I'd been led to believe was true.

100 Years Later: Review of "Tulsa 1921: Reporting a Massacre" by Randy Krehbiel

Reading Tulsa 1921 is a little like being in the middle of a mob and hearing all the hundred-year-old voices at once. It is an important record of absolutely everything leading up to, during, and after the mass killing of Black people in and the destruction of the Greenwood district, the Black Wall Street section, of Tulsa, Oklahoma on May 31–June 1, 1921—a history that was never recorded in Oklahoma school books and certainly did not make its way into my white high school history classes in suburban New York in the 1960s. But unless you are digging for facts, it is a difficult book to follow as it is really more like investigative notes, leaving nothing out. Often the reporting is recounting what is essentially a game of "Telephone" where facts are skewed or made up out of whole cloth or maybe not, and every single one of them is relayed for examination. According to author journalist Randy Krehbiel, some truths will never be known, especially about the incident that led to this abomination.

I was willing and eager to dig through this book because my mother was born in Tulsa in 1921, and although she never spoke about it, or is it possible she didn't know?—I'll never know—I suspect that whatever happened exploded into our family with such force that, unbeknownst to me, I've suffered the reverberations in my own history, due to my mother's trauma ... due to her parents' trauma … due to her Jewish merchant father's decision to inexplicably flee (my word, not hers—she never explained it and I don't know exactly when he fled, if he did indeed flee) Tulsa after she was born, four months after the massacre. The family subsequently moved so often that my mother suffered a lifelong phobia about being lost.

I'm glad this record exists. It made the people and the place real for me and I did pick up bits of history that may add to my personal understanding: the fact that the riot and destruction began in the white business district (where my grandfather's jewelry store probably was), although this pales in comparison to what followed; and the fact that at least two businesses mentioned in Greenwood (a movie theater and a grocery) had white owners, so perhaps there were others. But all this is tangential to what we need to know to understand what happened. Read More

Old Novels as Therapy

I am a published novelist and a rabid reader, but I've been stalled in both those areas. Between the cultural tumult and my almost-15-year-old dog's terminal kidney disease, I've become a worried political activist and an exhausted canine hospice caregiver.

I have two novels circulating to publishers through my agent (the newest of which deals with the cultural and political turmoil we are all living through right now), but since there is no discernible response, I see no point writing more—which nicely compliments my complete lack of inspiration.

Between my dog's IV drips and endless treks up and down my four flights of stairs to walk her, I found I cannot concentrate on reading new novels, let alone meeting new characters and remembering who everybody is. So suddenly my reading habit—a great source of joy—stalled.

In these incredibly dark days, I've found solace talking to people I've known since childhood. And, likewise, I realized I need books with a personal foundation already in place: books that I already know are outstanding, that I know will transport me—books that I trust because of my long history with them. I have such books already on my shelves, but I also bought a couple more.

Complete article published in the January 4, 2021 issue of Publishers Weekly.